![]()

A

native pig project in Bondoc Peninsula succeeds in raising income of farmers by P33,700 in two years just from

selling piglets and opens bigger opportunities for them to sell the specialty “Lechon.”

![philippine native pigs]()

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) is replicating the success of this native pigs multiplier project funded by the Bureau of Agricultural Research (

BAR). It is implemented by the University of the

Philippines Los Banos (

UPLB) Agricultural Systems Cluster-College of Agriculture.

It is in two barangays located in two municipalities in Bondoc Peninsula, Quezon—Brgy. Latangan of Mulanay and Brgy. San Juan of San Narciso.

Rural farmers’ income there traditionally reaches to only P5,000 to P6,000 yearly according to ipon-philippines.org.

That is being raised by the Native

Swine Project (NSP) by two to three times .

“A farmer with two sows, each producing seven weanlings three times in two years will have added income of P33,700 from piglet sales alone,” said Dr. Mary Jean G. Bulatao,

UPLB Native

Swine Project (NSP) team leader.

BAR is committed to implementing Phase 2 which expands the program to Real and Infanta, also in Quezon. The first phase was implemented from July 2009 to October 2011.

“We want to raise livelihood opportunities in these mostly upland areas. Their increased

production of native hogs will also enable them to meet a requirement for a specialty product that has a growing market in

Metro Manila,” said BAR Director Nicomedes P. Eleazar.

Dos por Cinco

The native swine project’s production and repayment scheme have worked well in the selected Bondoc Peninsula communities.

Each farmer-beneficiary received two ready-to-breed gilts (the Dos part). This enabled farmers to have a year-round supply of piglets.

As observed in the community, a native sow normally farrows or gives birth to piglets two times in 14 months. This produces an average of 28 piglets.

The project also provided five weanlings or piglets (the Cinco part) to farmers for immediate fattening. This should generate cash to farmers in three to four months.

That’s cash while they are waiting for the gilts (young female pig) to produce piglets.

Hardwork

Dos por Cinco is not just a dole out system that is here today and gone tomorrow. It encourages farmers to work hard by contributing something to it. That is land, at least a 1,000 square meters (sq.m), and labor.

They had to plant their farms with feed resources (such as Gabing san fernando,

madre de agua, and some

herbal plants for supplements. A main feed resource is the Gabing San Fernando (GSF).

GSF corm is reported by UPLB Researcher Virgilio T. Villancio to be capable of substituting

corn by 60 to 90 percent as the feed ingredient’s energy source.

Farmers also had to grow GSF and

Trichantera or

madre de agua. They had to construct a simple animal shed to protect animals from harsh environment. They had to care for the animals, put up fences in order to block stray animals from destroying the farm.

GSF corm is a tubelike portion of the GSF’s stembase and forms part of the main root system. It is also used as a planting material. It is locally called “sakwa” or “bungo” in Bondoc Peninsula.

“The project promoted the use of sakwa (a by-product) as the main source of energy feed for ranging native swine to improve nutrient availability and increase the average daily gain of the animals,” said Bulatao.

Profitable

Native pig

business can be profitable.

For a 25-kilo pig, a farmer can enjoy a P780 income per head. If a farmer decides to raise five heads in one cycle (five to six months), or a total of 10 heads per year, he will have an added income of P7,800 yearly.

Based on the project’s data, native sows can produce an average of seven live piglets in a litter. A farmer with two sows producing seven weanlings each, two times in 14 months , can have an added income of about P22,484 in 14 months or about P33,700 per two years from piglets alone.

“These may be modest added returns but very important to the farmers. These become a significant buffer income in times of unexpected needs. Farmers are now starting to treat this activity as a

business enterprise,” said Bulatao.

Weight gain

The improvement in the quality of

feeds given by the farmers to their native pigs from farmers’ own feed garden raised the average daily gain (ADG) of the native pigs.

The farmers were encouraged that they can earn higher from the GSF feeding. And that is without changing much of their traditional pig growing practices.

ADG for San Narciso was 0.13 kilos and Mulanay, 0.12 kilos. That is a significant improvement of at least 33 percent from their previous 0.09 kilos daily weight gain. Slaughter weight of animals is 15 to 30 kilos.

Higher ADG cut the fattening period of a 21-kilo pig by one month. That’s an important opportunity to turn

money around over a shorter time.

Paying back

Farmers pay for the

Dos por Cinco gilts and fattening weanlings by giving back piglets.

They are considered

debt-free once they give back the number of piglets whose price is equal to the purchase cost of the loaned animals.

Their piglet payments become part of a multiplier program. These are re-loaned to other organization members.

At the start, the project had 12 farmer partners—six in each of the barangay pilot areas. Beneficiaries are now at least 45 including the original 12 farmers, (as of this May 2013 at least 54 farmers), a 300 percent growth!

In two years, animal inventory of the farmers increased by 50 to 100 percent, while household income was up by 50 percent. Repayment is placed at 80 percent.

Because authorities saw how the NSP beneficiaries multiplied fast with good repayment rate, the FAO-International Labor Organization Livelihood Project adapted the Dos por Cinco scheme.

It operates in the same area. It provided the Dos por Cinco package or module to an additional 35 RIC (Rural Improvement Club) members in the Mulanay site.

The pig module (with two gilts, five weanlings) per farmer costs around P15,000.

Moreover, the local government of San Narciso also released some funds to benefit an additional three to five farmers initially.

GSF is now a valued feed product with its cormlet as food and sakwa as feed. Sakwa for native swine feed is now sold at P120 per sack in the market. It was only thought as waste before and given away free-of-charge.

Value adding

Phase 2 is stepping up help to farmers by providing options in marketing.

The first is on value adding, particularly meat processing. It involves producing finished products like sausage, longganiza, or cut-up pork that will give them an even higher income.

A freezer and other basic equipment like vacuum packaging machine, meat grinder, and some tools will be provided to the organization .

Good Agricultural Practice and Good Manufacturing Practice will be observed to assure clean and safe meat for consumers.

The other choice is for the farmer organization to become an assembler or consolidator. It involves gathering the animals from individual farmer members and selling in bulk to the assemblers-truckers. They themselves may also transport the animals to

Metro Manila, acting as an assembler-trucker .

But they need to be able to gather at least 200 animals at a single time for the transport to be cost efficient.

These programs will channel to farmers a portion of the income that goes to assemblers, `traders-transporters-.

At present, the link between farmers and

lechon processors are the traders.

But in the future there is a plan to link the Bondoc Peninsula native pig producers (as an organization) to other processors and

lechon retail chains. This will market their hogs not only to Metro Manila but also to nearby urban centers like the cities of Lucena, San Pablo and Lipa.

Smaller margin

Farmers’ direct contact to market will raise their income. At present, they are losing income opportunities that normally go to middlemen or traders.

“The animals have to pass through the village agent then to the municipal agent-assembler before they are loaded for delivery to the lechon processor by the trucker-assembler,” she said.

For instance, for a small 17-kilo or less live pig , a farmer receives a farmgate price of P1,000. The agent resells this at P1,200. Then the trucker resells it at P1,600. The lechon processor sells at P2,244.

Healthy

It has been a tradition for

coconut farmer sin Bondoc Peninsula to

raise native pigs. They sell these for full sized lechon or for “Lechon de Leche,” a roasted pig in its tender meat and crispy skin.

Its preferable taste compared to commercial breeds may be attributed to the native breed. The flavor of native lechon is also attributed to the production system.

Being raised free-range (roaming under

coconut trees), the pigs become lean from the daily exercise and are able to access vegetation in the area.

Other herbs

The animals need other feed ingredients like the

Trichantera gigantea as protein source.

The native pigs’ feed is a combination of two or three of different feed ingredients that are boiled together.

The choices are GSF corm,

gabi tubers,

gabi leaves and trunks,

rice and

corn bran, matured coconut meat,

cassava,

banana trunk, market wastes, kitchen refuse, kangkong,

papaya, oraro rejects, malunggay, mixed vegetable refuse, ipil-ipil,

sweet potato leaves, Trichantera or Madre de Agua.

Boars and lactating sows are given

rice or corn bran added into cooked feed.

Feeding is two times a day.

Breeding program

The ongoing Phase 2 will also involve breeding. It has a partnership with the Bureau of Animal Industry (BAI)-National Swine and Poultry Research and Development Center based in Tiaong, Quezon. BAI is engaged in a study on “Animal Genomics to Increase Productivity

Part of the BAI-NSPRDC project is to characterize and conserve the Philippine native pigs. .

Bulatao said this is of the essence.

“While native pigs are considered disease resistant compared to commercial breed, the project still encountered mortality due to disease,” she said.

Native pigs, unlike the imported white breeds, are usually colored black or have spots.

Production

As of July 2011, the San Narciso site produced a total of 173 animals. These were 15 breeders, 110 weaners, and 48 piglets. The Mulanay site produced 189 animals. These were 15 breeders, 128 weaners, and 46 piglets.

After six-seven months of planting GSF, farmers’ fields yielded an average of 240 kilos of fresh GSF tuber per 1,000 sq.m.(2.4 tons per hectare).

In Brgy. San Narciso, after seven months, farmers produced 2.2 tons per hectare of sakwa; 2.4 tons per hectare of gabi; and 7.6 tons per hectare of herbage)

In Brgy. Mulanay, after six months, farmers produced 390 kilos of sakwa per 1,000 sq.m., 6,420 kilos of gabi over the same area, and 760 kilos of herbage.

San Narciso farmers sold their pigs at P94 per kilo of live weight while Mulanay, at P90 per kilo.

Weanlings were priced P800 to P1,000 per head.

Average farm gate price of native pigs per head was P2,161 for Mulanay for an average weight of 24.49 kilos and P1,787 per head for San Narciso for an average weight of 19.03 kilos.

Bondoc Peninsula

The farmers in the pilot program in Brgy. Latangan, Mulanay came from the Rural Improvement Club (RIC), a women’s group supported by the town local government unit. A total of 22 out of 43 RIC members became partners at the end of two years.

“The number is continuously growing as other members await their turns to receive five heads of native swine,” said Bulatao.

In San Narciso, the farmers already formed a group-- San Juan Native Swine Producers Association.

Farmers underwent training and visited the National Swine and Poultry Research and Development Center in Tiaong, Quezon and the Animal and Dairy Sciences Cluster Farm in UP Los Banos.

They were trained on Good Agricultural Practices to improve their native pig production practices including prevention and management of common swine diseases. It also included preparation of common herbal supplements to improve animal health and reduce mortality.

They were also taught on record keeping and financial management.

###

For any questions, please call Dr. Mary Jean G. Bulatao, UPLB-CA; for interview requests, Ms. Analiza C. Mendoza, 0923-436-3177

Advantages of using Profitable Innovative Growing System (PIGS)

- Solves bad odor and health risks in piggeries

- Easier, cleaner, and cost-effective

- Reduces antibiotic dependency in swine

- Environment and community-friendly

- Health protection for both humans and animals

- Promotes humane animal treatment

Guidelines in Constructing an Odorless Pigpen/ Odor-free Piggery

- Avoid lowland where flood incidence is high during rainy season

- Soil or earth flooring must be above the highest possible water level in case of flood

- Piggery must have adequate wind and sunlight penetration

- General bedding requirement is at least one and a half (1.5) square meters per pig

- Place 2 to 3 foot deep newly milled rice hull or other organic materials above the earth/soil flooring to act as bedding for the pigs

- Wallowing pond should be 1 meter wide spanning the length of the pen with water depth of 1 to 4 inches deep depending on the size of the pig

- Feeding trough should be constructed opposite the wallowing pond and should be 11 inches from the wall of the pen

- Use concrete hollow blocks for the lower fencing around the pen, for the wallowing pool, and feeding troughs

- Use iron bars or matured bamboos as upper fencing to allow for wind to pass through and to prevent pigs from jumping out of the pen

Managing an Odorless Pigpen/ Odor-free Piggery

- Change the water in the wallowing pond everyday

- Provide unlimited clean drinking water

- Follow the prescribed feeding guide

- After harvest, the rice hull bedding can be used as compost or plant fertilizer

Watch the Video on How To Set Up PIGS Babuyang Walang Amoy

Source: babuyangwalangamoy.com

Advantages of using Profitable Innovative Growing System (PIGS)

- Solves bad odor and health risks in piggeries

- Easier, cleaner, and cost-effective

- Reduces antibiotic dependency in swine

- Environment and community-friendly

- Health protection for both humans and animals

- Promotes humane animal treatment

Guidelines in Constructing an Odorless Pigpen/ Odor-free Piggery

- Avoid lowland where flood incidence is high during rainy season

- Soil or earth flooring must be above the highest possible water level in case of flood

- Piggery must have adequate wind and sunlight penetration

- General bedding requirement is at least one and a half (1.5) square meters per pig

- Place 2 to 3 foot deep newly milled rice hull or other organic materials above the earth/soil flooring to act as bedding for the pigs

- Wallowing pond should be 1 meter wide spanning the length of the pen with water depth of 1 to 4 inches deep depending on the size of the pig

- Feeding trough should be constructed opposite the wallowing pond and should be 11 inches from the wall of the pen

- Use concrete hollow blocks for the lower fencing around the pen, for the wallowing pool, and feeding troughs

- Use iron bars or matured bamboos as upper fencing to allow for wind to pass through and to prevent pigs from jumping out of the pen

Managing an Odorless Pigpen/ Odor-free Piggery

- Change the water in the wallowing pond everyday

- Provide unlimited clean drinking water

- Follow the prescribed feeding guide

- After harvest, the rice hull bedding can be used as compost or plant fertilizer

Watch the Video on How To Set Up PIGS Babuyang Walang Amoy

Source: babuyangwalangamoy.com

That should contribute over the long term to raising the country’s milk production, according to PCC Supervising Science Research Specialist Jesus Rommel V. Herrera.

The country is hardly a producer of milk and dairy products with importation around $500-$600 million yearly.

“We will improve our selection scheme for dairy buffaloes by integrating

That should contribute over the long term to raising the country’s milk production, according to PCC Supervising Science Research Specialist Jesus Rommel V. Herrera.

The country is hardly a producer of milk and dairy products with importation around $500-$600 million yearly.

“We will improve our selection scheme for dairy buffaloes by integrating

Photo by

Photo by

Photo by

Photo by

How to Raise Cattle

Types of Cattle Raising

1. Cow-Calf Operation

2.

How to Raise Cattle

Types of Cattle Raising

1. Cow-Calf Operation

2.  Guide in Selecting Stocks Based on Physical Appearance

Selecting Cows and Heifers for Breeding

* Milking ability and feminity

Mild maternal face with bright and alert eyes, good disposition, and quiet temperament.

An udder of good size and shape. An udder that is soft, flexible, and spongy to the touch, not fleshlike and hard, is expected to secrete more milk.

* Age

In general, beef cows remain productive for 13 years if they start calving at three years of age. They are most productive from four to eight years of age.

* Breeding ability and ancestry

Cows that calve regularly are desirable. Calves from cows that do not take on flesh readily do not give much profit. In buying heifers for foundation stock, select those which belong to families which have regularly produced outstanding calves.

* Types and conformation

An ideal cow has a rectangular frame. Should be of medium width between the thurls and pins to have necessary frame on which to hang profitable beef. The rump must be long and smooth.

Selecting a Bull

* Physical appearance

A fairly good middle or barrel indicates a well-developed digestive system and healthy vital organs such as the heart, liver, and lungs. Likewise, a full heart girth, broad muzzle, large nostrils, muscular checks and jaw, well-rounded thighs, and a full loin, make up a good constitution. A bull with these qualities is desirable.

The legs of a bull should be strong enough to carry its own weight and to carry him around to look for cows that are in heat and to search for food when necessary. Successful mating of cows is insured when a bull has strong legs.

* Sex character

Well-developed sex organs are characterized by fully descended testicles, deep wide chest, and broad head. These qualities indicate virility and good reproduction.

Selecting Cattle for Fattening

* Age

Young animals have striking advantages over older cattle. They need less feed for every unit gain in weight because they can masticate and ruminate thoroughly and can consume more feed in proportion to their body weight. Their increase in weight is due partly to the growth of muscles and vital organs. In older cattle the increase is largely due to fat deposits.

On the other hand, older animals as feeder stock also have advantages. Generally, a two-year old steer will require a shorter feeding period than a calf or a yearling because the latter grows while it fattens. Calves are choosy when given coarse and stemmy roughage, while two-year old steers utilize large quantities of roughage to produce fat primarily because they have a better capacity to digest. In most cases, they readily relish the

Guide in Selecting Stocks Based on Physical Appearance

Selecting Cows and Heifers for Breeding

* Milking ability and feminity

Mild maternal face with bright and alert eyes, good disposition, and quiet temperament.

An udder of good size and shape. An udder that is soft, flexible, and spongy to the touch, not fleshlike and hard, is expected to secrete more milk.

* Age

In general, beef cows remain productive for 13 years if they start calving at three years of age. They are most productive from four to eight years of age.

* Breeding ability and ancestry

Cows that calve regularly are desirable. Calves from cows that do not take on flesh readily do not give much profit. In buying heifers for foundation stock, select those which belong to families which have regularly produced outstanding calves.

* Types and conformation

An ideal cow has a rectangular frame. Should be of medium width between the thurls and pins to have necessary frame on which to hang profitable beef. The rump must be long and smooth.

Selecting a Bull

* Physical appearance

A fairly good middle or barrel indicates a well-developed digestive system and healthy vital organs such as the heart, liver, and lungs. Likewise, a full heart girth, broad muzzle, large nostrils, muscular checks and jaw, well-rounded thighs, and a full loin, make up a good constitution. A bull with these qualities is desirable.

The legs of a bull should be strong enough to carry its own weight and to carry him around to look for cows that are in heat and to search for food when necessary. Successful mating of cows is insured when a bull has strong legs.

* Sex character

Well-developed sex organs are characterized by fully descended testicles, deep wide chest, and broad head. These qualities indicate virility and good reproduction.

Selecting Cattle for Fattening

* Age

Young animals have striking advantages over older cattle. They need less feed for every unit gain in weight because they can masticate and ruminate thoroughly and can consume more feed in proportion to their body weight. Their increase in weight is due partly to the growth of muscles and vital organs. In older cattle the increase is largely due to fat deposits.

On the other hand, older animals as feeder stock also have advantages. Generally, a two-year old steer will require a shorter feeding period than a calf or a yearling because the latter grows while it fattens. Calves are choosy when given coarse and stemmy roughage, while two-year old steers utilize large quantities of roughage to produce fat primarily because they have a better capacity to digest. In most cases, they readily relish the

The rapid development in recent years of Asia’s livestock industry has been matched by the huge increase in the importation of livestock feed. Feed costs are not only a burden on the national budget of nearly every Asian country, they are also a burden on the budget of livestock farms, where they are often 60% or more of total production costs. Even in Thailand, which is one of the few Asian countries to produce a surplus of feed materials, small-scale farmers often cannot afford enough feed to maintain their livestock in good condition over the dry season. Throughout the region, cost and availability of feed are probably the most important constraint to increased livestock production.

The rapid development in recent years of Asia’s livestock industry has been matched by the huge increase in the importation of livestock feed. Feed costs are not only a burden on the national budget of nearly every Asian country, they are also a burden on the budget of livestock farms, where they are often 60% or more of total production costs. Even in Thailand, which is one of the few Asian countries to produce a surplus of feed materials, small-scale farmers often cannot afford enough feed to maintain their livestock in good condition over the dry season. Throughout the region, cost and availability of feed are probably the most important constraint to increased livestock production.

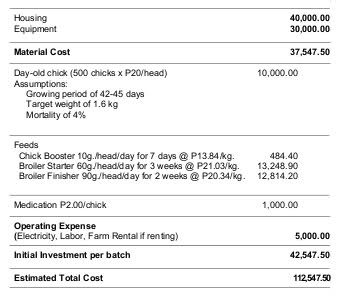

I. Estimated Investment Cost

I. Estimated Investment Cost

II. Selection of Stock to Raise

• Stock should be purchased from a reliable hatchery or dealer where the parent stocks are well housed and well managed.

• Select/buy only healthy chicks (i.e. dry, fluffy feathers, bright eyes, and alert and active appearance; free from diseases, and abnormalities; chicks should have uniform size and color; and in the case of broiler chicks, it should be less than 33 g. at day- old)

• Choose those that have high livability and are fast growers.

III. Rearing of the Day-Old Chicks

• Provide sufficient artificial heat to keep day-old chicks warm during the day and night. Avoid abrupt changes in brooder temperature during the first two weeks of life.

• Provide adequate space for chicks as they grow. Overcrowding is one of the factors affecting poor growth. Good ventilation also helps avoid future respiratory diseases. Also, provide a good light source as a well-lighted brooder encourages chicks to start feeding.

• Provide the chicks with good quality feeds either home grown or commercially sourced. Feed the chicks intermittently rather than continuously. Research studies have shown that chicks utilize nutrients better when using intermittent feeding. Do not allow feed troughs to go empty for more than 1-2 hours.

• Cleanliness and dryness of the brooding quarters will prevent chicks’ contamination from parasites and diseases, which might have been carried by previously brooded chicks.

• Environment should be kept as uniform as possible. Sudden changes in the surroundings cause a certain degree of stress or insecurity (e.g. removal of brooder canopy; slamming doors of brooder houses; or the presence of drafts). It is advisable that a regular caretaker feed the chicks following a definite schedule during the first three weeks of the chick’s life.

• Make sure that feeds and fresh water are always available.

Vitamins, minerals, and antibiotic supplements may be added to the drinking water during the first few days. Consult your feed dealer.

• Always check the chicks at night before going to sleep.

• All weak, deformed, and sickly chicks should be culled right away and disposed of properly.

• The immediate burning or burying of dead birds is an important part of a good sanitation program. Do not expose to flies or rats.

IV. Rearing of the Growing Stock

• Broilers are marketed when they reach 45-60 days of age depending on strain.

• Birds are given anti-stress drugs, either in the feed or in the drinking water, 2-5 days before and after they are transferred to the growing houses.

• Thoroughly clean and disinfect the growing houses prior to the transfer of the growing stock. Transfer birds only during good weather.

• During summer, birds’ appetite diminishes but this may be sufficiently restored by wet mash feeding or by taking appropriate measures like spraying, misting, or sprinkling the roofing with water to lower house temperature.

V. Housing

Chickens, being warm blooded, have the ability to maintain a rather uniform temperature of their internal organs. However, the mechanism is efficient only when the ambient temperature is within certain limits. Birds cannot adjust well to extremes; therefore, it is very important that chickens be housed, cared and provided with an environment that will enable them to maintain their thermal balance.

• If possible, the length of the broiler house should run from east to west. This prevents direct sunlight from penetrating the side walls of the house, which could cause heat build-up inside.

• Ventilation is very important. Allocate at least 1 square foot of floor space per bird.

• If constructing an open-sided type of housing, elevate the house about 1.5 m. from the ground. This ensures proper circulation of air and easier collection of fecal matter underneath the house after each harvest.

• The building should be rat proof, bird proof, and cat proof.

• Trees may be planted on the sides of the house to provide shade during hot season. These can also serve as protection from storms or weather disturbances.

• The roofing should be monitor-type and high enough to provide better air circulation inside the broiler house.

• In preparation for the arrival of the chicks, thoroughly clean the house with the use of a high pressure washer to remove dust, fecal matter, or any debris inside. Disinfect the house and all equipment to be used.

VI. Location Requirements and Recommended Layout for Poultry Farms

• A poultry farm must be located outside urban areas.

• It must be located in 25 m. radius from sources of ground and surface drinking water.

• Medium and large poultry farms must be at least 1,000 m. away from built-up areas (residential, commercial, institutional and industrial) while a small scale must be at least 500 m. away from these areas.

VII. Feeding Management

• Broiler-commercial rations are fed to the birds during the first 5 weeks and from then on are replaced by the broiler-finisher ration.

• All purpose straight broiler ration is fed from the start to the marketing age of eight weeks.

• Commercial broiler feeds contain additives considered to be grown-promoting substances. Feed additives make broiler production profitable and help broiler farmer control diseases.

VIII. Health Management

• The most economical and ideal method to control diseases could be achieved by proper management, good sanitation, and having an effective vaccination program. Consult a veterinarian for a program suited to your business operation.

IX. Marketing

• Alternative market outlets should be surveyed even before deciding to start a broiler business to ensure a ready market at the time of harvest. Marketing arrangements with local hotels, restaurants, cafeterias, institutional buyers, and grocery stores with freezers may be made.

• Producers may form associations or market cooperatives so that they could agree on a common price. Organized producers have bargaining power with regard to their selling prices.

• Producers are advised to compute which is more profitable to sell, the birds dressed or live, and whether to sell at the farm or in the market.

• The broilers should be sold at optimum weight (1.6-1.9 kg. live weight).

X. Estimated Income per Batch (42-45 days)

* Net of 4% mortality rate

** Based on DA-BAI figures as of Feb 2, 2009

XI. Ecological Implications

Livestock production impacts on the environment through possible effects on surface and ground water quality, gas emissions from animal wastes, and unpleasant odors arising from the enterprise.

Manure management is less problematic in poultry enterprises, where manure management does not usually entail wet disposal as in piggery enterprises, and where the chicken dung is often routinely collected for conversion into organic fertilizer or fish feeds.

Gases emitted in livestock enterprises include ammonia, carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide. The latter three contribute to atmospheric changes that lead to global warming. Unpleasant odors emanating from a livestock enterprise are a function of the scale of operation and sound manure management.

It is likely that the increasing scale of operation in livestock enterprises in the past years has also intensified the adverse environmental impacts of the industry. The challenge is to constantly develop more efficient and effective technologies for managing animal wastes tailored to different scales of production, even as various means of converting such wastes to useful products (e.g. biogas, fertilizer) have been in use for many years.

XII. Registration Requirements

1. Business Name Registration

From the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) provincial office of the province where the business is located

Validity: 5 years

2. Barangay Clearance

From the barangay office, which has jurisdiction over the area where the business is located

3. Mayor’s Permit and License / Sanitary Permit

From the local government which has jurisdiction over the area where the business is located

Validity: 1 year

4. Tax Identification Number (TIN)

From the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) National Office

Diliman, Quezon City or from the nearest BIR Office in your locality

5. Environmental Compliance Certificate

Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR)

Visayas Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City

Telephone No.:: (632) 929.6626

XIII. Financing

Agricultural Credit Policy Council (ACPC)

28/F, One San Miguel Avenue Building

San Miguel Avenue, Ortigas Center Pasig City

Telephone Nos.: 634.3326 / 634.3320 to 21

Telefax: 636.3393

Land Bank of the Philippines (LBP)

Head Office: 1598 M. H. Del Pilar cor. Dr. J. Quintos Sts.

Malate, Manila

Telephone Nos.: 522.0000 / 551.2200

Development Bank of the Philippines (DBP)

Head Office: Sen. Gil J. Puyat Avenue cor. Makati Avenue

Makati City

Telephone No.: 818.9511 (connect to SME Department)

XIV. Technical Assistance

Department of Agriculture

Bureau of Animal Industry (DA-BAI)

Visayas Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City

Telephone No.: (632) 926.6883

Fax No.: 927.0971

Technology Resource Center (TRC)

TRC Building,103 J. Abad Santos cor. Lopez Jaena Sts.,

Little Baguio, San Juan City (Near corner Wilson Street)

Telephone No.: (632) 727.6205

Philippine Association of Broiler Integrators, Inc. (PABI)

c/o San Miguel Foods, Inc.

18/F, JMT Building, ADB Avenue, Ortigas Center, Pasig City

Telephone No.: 634.1010

Telefax: 637.3786

Download here the

II. Selection of Stock to Raise

• Stock should be purchased from a reliable hatchery or dealer where the parent stocks are well housed and well managed.

• Select/buy only healthy chicks (i.e. dry, fluffy feathers, bright eyes, and alert and active appearance; free from diseases, and abnormalities; chicks should have uniform size and color; and in the case of broiler chicks, it should be less than 33 g. at day- old)

• Choose those that have high livability and are fast growers.

III. Rearing of the Day-Old Chicks

• Provide sufficient artificial heat to keep day-old chicks warm during the day and night. Avoid abrupt changes in brooder temperature during the first two weeks of life.

• Provide adequate space for chicks as they grow. Overcrowding is one of the factors affecting poor growth. Good ventilation also helps avoid future respiratory diseases. Also, provide a good light source as a well-lighted brooder encourages chicks to start feeding.

• Provide the chicks with good quality feeds either home grown or commercially sourced. Feed the chicks intermittently rather than continuously. Research studies have shown that chicks utilize nutrients better when using intermittent feeding. Do not allow feed troughs to go empty for more than 1-2 hours.

• Cleanliness and dryness of the brooding quarters will prevent chicks’ contamination from parasites and diseases, which might have been carried by previously brooded chicks.

• Environment should be kept as uniform as possible. Sudden changes in the surroundings cause a certain degree of stress or insecurity (e.g. removal of brooder canopy; slamming doors of brooder houses; or the presence of drafts). It is advisable that a regular caretaker feed the chicks following a definite schedule during the first three weeks of the chick’s life.

• Make sure that feeds and fresh water are always available.

Vitamins, minerals, and antibiotic supplements may be added to the drinking water during the first few days. Consult your feed dealer.

• Always check the chicks at night before going to sleep.

• All weak, deformed, and sickly chicks should be culled right away and disposed of properly.

• The immediate burning or burying of dead birds is an important part of a good sanitation program. Do not expose to flies or rats.

IV. Rearing of the Growing Stock

• Broilers are marketed when they reach 45-60 days of age depending on strain.

• Birds are given anti-stress drugs, either in the feed or in the drinking water, 2-5 days before and after they are transferred to the growing houses.

• Thoroughly clean and disinfect the growing houses prior to the transfer of the growing stock. Transfer birds only during good weather.

• During summer, birds’ appetite diminishes but this may be sufficiently restored by wet mash feeding or by taking appropriate measures like spraying, misting, or sprinkling the roofing with water to lower house temperature.

V. Housing

Chickens, being warm blooded, have the ability to maintain a rather uniform temperature of their internal organs. However, the mechanism is efficient only when the ambient temperature is within certain limits. Birds cannot adjust well to extremes; therefore, it is very important that chickens be housed, cared and provided with an environment that will enable them to maintain their thermal balance.

• If possible, the length of the broiler house should run from east to west. This prevents direct sunlight from penetrating the side walls of the house, which could cause heat build-up inside.

• Ventilation is very important. Allocate at least 1 square foot of floor space per bird.

• If constructing an open-sided type of housing, elevate the house about 1.5 m. from the ground. This ensures proper circulation of air and easier collection of fecal matter underneath the house after each harvest.

• The building should be rat proof, bird proof, and cat proof.

• Trees may be planted on the sides of the house to provide shade during hot season. These can also serve as protection from storms or weather disturbances.

• The roofing should be monitor-type and high enough to provide better air circulation inside the broiler house.

• In preparation for the arrival of the chicks, thoroughly clean the house with the use of a high pressure washer to remove dust, fecal matter, or any debris inside. Disinfect the house and all equipment to be used.

VI. Location Requirements and Recommended Layout for Poultry Farms

• A poultry farm must be located outside urban areas.

• It must be located in 25 m. radius from sources of ground and surface drinking water.

• Medium and large poultry farms must be at least 1,000 m. away from built-up areas (residential, commercial, institutional and industrial) while a small scale must be at least 500 m. away from these areas.

VII. Feeding Management

• Broiler-commercial rations are fed to the birds during the first 5 weeks and from then on are replaced by the broiler-finisher ration.

• All purpose straight broiler ration is fed from the start to the marketing age of eight weeks.

• Commercial broiler feeds contain additives considered to be grown-promoting substances. Feed additives make broiler production profitable and help broiler farmer control diseases.

VIII. Health Management

• The most economical and ideal method to control diseases could be achieved by proper management, good sanitation, and having an effective vaccination program. Consult a veterinarian for a program suited to your business operation.

IX. Marketing

• Alternative market outlets should be surveyed even before deciding to start a broiler business to ensure a ready market at the time of harvest. Marketing arrangements with local hotels, restaurants, cafeterias, institutional buyers, and grocery stores with freezers may be made.

• Producers may form associations or market cooperatives so that they could agree on a common price. Organized producers have bargaining power with regard to their selling prices.

• Producers are advised to compute which is more profitable to sell, the birds dressed or live, and whether to sell at the farm or in the market.

• The broilers should be sold at optimum weight (1.6-1.9 kg. live weight).

X. Estimated Income per Batch (42-45 days)

* Net of 4% mortality rate

** Based on DA-BAI figures as of Feb 2, 2009

XI. Ecological Implications

Livestock production impacts on the environment through possible effects on surface and ground water quality, gas emissions from animal wastes, and unpleasant odors arising from the enterprise.

Manure management is less problematic in poultry enterprises, where manure management does not usually entail wet disposal as in piggery enterprises, and where the chicken dung is often routinely collected for conversion into organic fertilizer or fish feeds.

Gases emitted in livestock enterprises include ammonia, carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide. The latter three contribute to atmospheric changes that lead to global warming. Unpleasant odors emanating from a livestock enterprise are a function of the scale of operation and sound manure management.

It is likely that the increasing scale of operation in livestock enterprises in the past years has also intensified the adverse environmental impacts of the industry. The challenge is to constantly develop more efficient and effective technologies for managing animal wastes tailored to different scales of production, even as various means of converting such wastes to useful products (e.g. biogas, fertilizer) have been in use for many years.

XII. Registration Requirements

1. Business Name Registration

From the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) provincial office of the province where the business is located

Validity: 5 years

2. Barangay Clearance

From the barangay office, which has jurisdiction over the area where the business is located

3. Mayor’s Permit and License / Sanitary Permit

From the local government which has jurisdiction over the area where the business is located

Validity: 1 year

4. Tax Identification Number (TIN)

From the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) National Office

Diliman, Quezon City or from the nearest BIR Office in your locality

5. Environmental Compliance Certificate

Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR)

Visayas Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City

Telephone No.:: (632) 929.6626

XIII. Financing

Agricultural Credit Policy Council (ACPC)

28/F, One San Miguel Avenue Building

San Miguel Avenue, Ortigas Center Pasig City

Telephone Nos.: 634.3326 / 634.3320 to 21

Telefax: 636.3393

Land Bank of the Philippines (LBP)

Head Office: 1598 M. H. Del Pilar cor. Dr. J. Quintos Sts.

Malate, Manila

Telephone Nos.: 522.0000 / 551.2200

Development Bank of the Philippines (DBP)

Head Office: Sen. Gil J. Puyat Avenue cor. Makati Avenue

Makati City

Telephone No.: 818.9511 (connect to SME Department)

XIV. Technical Assistance

Department of Agriculture

Bureau of Animal Industry (DA-BAI)

Visayas Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City

Telephone No.: (632) 926.6883

Fax No.: 927.0971

Technology Resource Center (TRC)

TRC Building,103 J. Abad Santos cor. Lopez Jaena Sts.,

Little Baguio, San Juan City (Near corner Wilson Street)

Telephone No.: (632) 727.6205

Philippine Association of Broiler Integrators, Inc. (PABI)

c/o San Miguel Foods, Inc.

18/F, JMT Building, ADB Avenue, Ortigas Center, Pasig City

Telephone No.: 634.1010

Telefax: 637.3786

Download here the

The underlying principle is, that the chickens will eat their feathers to get the protein they need. The chickens feathers and their fellow chicken's skins are good sources of protein.

Tips showing when chickens are supplied with more protein are: when the chickens are bald, when chickens are suffering from wounds inflicted by other chickens that peck on them and when less feathers are scattered around.

These techniques could easily be adapted to large scale commercial operations where collection of accurate weight and conversion data would not be possible.

Source: Greenfields, July 1980

The underlying principle is, that the chickens will eat their feathers to get the protein they need. The chickens feathers and their fellow chicken's skins are good sources of protein.

Tips showing when chickens are supplied with more protein are: when the chickens are bald, when chickens are suffering from wounds inflicted by other chickens that peck on them and when less feathers are scattered around.

These techniques could easily be adapted to large scale commercial operations where collection of accurate weight and conversion data would not be possible.

Source: Greenfields, July 1980

Photo by

Photo by

Goat raising needs a year-round supply of feeds. In the Philippines, feeds are abundant during the wet season but scarce during the dry season. Hence, processing feeds through pelleting is important. A pellet is a small, solid or densely packed mass of feeds.

Pellet feeds for goats are complete feeds formulated by pelleting feed ingredients needed to supply the animals’ nutritional needs for growth and lactation.

Some of the ingredients that can be pelletized are Ipil-ipil, kakawate, and rensonii; concentrates; and mineral supplements.

Ipil-ipil, kakawate, and rensonii can be processed into leaf meal as the protein source in the goat’s diet. Concentrates provide most of the energy as well as true protein needed by the animals. Mineral supplements, on the other hand, are important source of minerals such as calcium, phosphorus, sodium, and chloride.

The palletized feed provides certain advantages. It makes feeding more efficient; enables animal raisers to obtain better quality of feeds, reduces labor, increases productivity because of faster growth rate of goats and more milk yield from lactating goats; requires lesser space during storage and can be stored at room temperature.

Cost of producing the pellets for growing goats is P9.64 per kilogram and P10.01 per kilogram for lactating goats. Cost could vary depending on the raw materials used and their prevailing prices. The feeds can be sold at P11.00 per kilogram for growing goats and P11.50 per kilogram for lactating goats. Gross return is estimated at P110,000 and P115,000 per 10,000 kg for growing and lactating goats, respectively.

Goat raising needs a year-round supply of feeds. In the Philippines, feeds are abundant during the wet season but scarce during the dry season. Hence, processing feeds through pelleting is important. A pellet is a small, solid or densely packed mass of feeds.

Pellet feeds for goats are complete feeds formulated by pelleting feed ingredients needed to supply the animals’ nutritional needs for growth and lactation.

Some of the ingredients that can be pelletized are Ipil-ipil, kakawate, and rensonii; concentrates; and mineral supplements.

Ipil-ipil, kakawate, and rensonii can be processed into leaf meal as the protein source in the goat’s diet. Concentrates provide most of the energy as well as true protein needed by the animals. Mineral supplements, on the other hand, are important source of minerals such as calcium, phosphorus, sodium, and chloride.

The palletized feed provides certain advantages. It makes feeding more efficient; enables animal raisers to obtain better quality of feeds, reduces labor, increases productivity because of faster growth rate of goats and more milk yield from lactating goats; requires lesser space during storage and can be stored at room temperature.

Cost of producing the pellets for growing goats is P9.64 per kilogram and P10.01 per kilogram for lactating goats. Cost could vary depending on the raw materials used and their prevailing prices. The feeds can be sold at P11.00 per kilogram for growing goats and P11.50 per kilogram for lactating goats. Gross return is estimated at P110,000 and P115,000 per 10,000 kg for growing and lactating goats, respectively.

The care of a small backyard poultry can help fill the family food requirements for eggs and meat. It can also be a source of additional income. A valuable by-product is the chicken manure which is a very excellent organic fertilizer for farm and home gardens.

The care of a small backyard poultry can help fill the family food requirements for eggs and meat. It can also be a source of additional income. A valuable by-product is the chicken manure which is a very excellent organic fertilizer for farm and home gardens.

Project scheme

1. Each participating family will start with two properly selected upgraded roosters and ten layers (inabin; five for egg production and five layers to produce chicks for meat production).

2. A poultry house should be constructed using local materials for minimum expense. The house should have perch racks, roosts, nests, feedhoppers and waterers. The house should at Ieast be 7 feet high, with a floor area of 10 fl x 12 fl. It can also be provided with a fenced area as run and a growing house for the chicks.

3. The family could buy or raise the feed supplements like co., sorghum, ipil-ipil and others.

4. Recommended management practices on feeding and watering, brooding and rearing young chicks, culling and selection, record keeping, etc., should be followed.

5. Regular immunization (1-2 times a year against poultry diseases like avian pest, CRD, fowl pox, etc.)

Feasibility study

1. Expenses

10 layers x P 40/layer = P400.00

2 roosters x P 50/rooster = 100.00

Housing and fence = 1,000.00

Vaccines/veterinary drugs = 25.00

Feed supplement = 500.00

Total = P 2,025.00

2. Egg Production Cycle

20 eggs/layer/month x 12 months = 240 eggs

240 eggs x 5 layers = 1,200 eggs/year

1,200 eggs/year x P 1.50/egg P 1,800.00

3. Meat Production Cycle

A. Growing period

Laying - 20 days

Incubation - 21 days

Brooding - 60 days

One production cycle = 101 days or 3 cycles per year

B. Production/Multiplication cycle

Survival rate of chicks/hen/cycle = 10 chicks

10 chicks x 3 cycles/year = 30 chicks

30 chicks x 5 hens = 150 chicks

Gross income from 5 hens/year

150 birds x P 30/bird P 4,500.00

4. Cost Analysis

Gross income from egg production = P1,800.00

Gross income from meat production = 4,500.00

Total income for 3 cycles (1 year) = P6,300.00

Less: Expenses = 2,025.00

Net income = P4,275.00

Note: The roosters remain. To prevent broodiness of native chickens after laying, it is advisable to dip the birds in water.

Home-made chicken feeds

4 cans yellow corn or broken rice (binlid)

1 1/2 cans rice bran (darak)

1 can dry fish meal or 2 parts fresh fish or ground snails

1 112 can copra oil meal

1/2 can copra oil meal

1/2 can ground mongo, sitao, patani or soy bean seeds

1/2 can dry ipil-ipil leaf meal

1 tablespoon salt 1 handful powdered shell/agricultural lime (apog)

Notes:

Use boiled gabi, ubi, cassava or camote as substitute for corn meal.

Double the recommended amounts if ingredients are not in dry form.

Use dried azolla or dried filter cake to replace part of the rice bran.

A. Other Low-cost Poultry Feeds

- bananas

- fly maggots

- fingerlings

- azolla

- snails

- filter cake (dried and good)

- termites

- earthworms

Filter cake is the dark brown-black sediment after clarification and filtration during the manufacture of sugar.

B. Anti-nutrients in Some Feeds.

Project scheme

1. Each participating family will start with two properly selected upgraded roosters and ten layers (inabin; five for egg production and five layers to produce chicks for meat production).

2. A poultry house should be constructed using local materials for minimum expense. The house should have perch racks, roosts, nests, feedhoppers and waterers. The house should at Ieast be 7 feet high, with a floor area of 10 fl x 12 fl. It can also be provided with a fenced area as run and a growing house for the chicks.

3. The family could buy or raise the feed supplements like co., sorghum, ipil-ipil and others.

4. Recommended management practices on feeding and watering, brooding and rearing young chicks, culling and selection, record keeping, etc., should be followed.

5. Regular immunization (1-2 times a year against poultry diseases like avian pest, CRD, fowl pox, etc.)

Feasibility study

1. Expenses

10 layers x P 40/layer = P400.00

2 roosters x P 50/rooster = 100.00

Housing and fence = 1,000.00

Vaccines/veterinary drugs = 25.00

Feed supplement = 500.00

Total = P 2,025.00

2. Egg Production Cycle

20 eggs/layer/month x 12 months = 240 eggs

240 eggs x 5 layers = 1,200 eggs/year

1,200 eggs/year x P 1.50/egg P 1,800.00

3. Meat Production Cycle

A. Growing period

Laying - 20 days

Incubation - 21 days

Brooding - 60 days

One production cycle = 101 days or 3 cycles per year

B. Production/Multiplication cycle

Survival rate of chicks/hen/cycle = 10 chicks

10 chicks x 3 cycles/year = 30 chicks

30 chicks x 5 hens = 150 chicks

Gross income from 5 hens/year

150 birds x P 30/bird P 4,500.00

4. Cost Analysis

Gross income from egg production = P1,800.00

Gross income from meat production = 4,500.00

Total income for 3 cycles (1 year) = P6,300.00

Less: Expenses = 2,025.00

Net income = P4,275.00

Note: The roosters remain. To prevent broodiness of native chickens after laying, it is advisable to dip the birds in water.

Home-made chicken feeds

4 cans yellow corn or broken rice (binlid)

1 1/2 cans rice bran (darak)

1 can dry fish meal or 2 parts fresh fish or ground snails

1 112 can copra oil meal

1/2 can copra oil meal

1/2 can ground mongo, sitao, patani or soy bean seeds

1/2 can dry ipil-ipil leaf meal

1 tablespoon salt 1 handful powdered shell/agricultural lime (apog)

Notes:

Use boiled gabi, ubi, cassava or camote as substitute for corn meal.

Double the recommended amounts if ingredients are not in dry form.

Use dried azolla or dried filter cake to replace part of the rice bran.

A. Other Low-cost Poultry Feeds

- bananas

- fly maggots

- fingerlings

- azolla

- snails

- filter cake (dried and good)

- termites

- earthworms

Filter cake is the dark brown-black sediment after clarification and filtration during the manufacture of sugar.

B. Anti-nutrients in Some Feeds.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) is replicating the success of this native pigs multiplier project funded by the Bureau of Agricultural Research (

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) is replicating the success of this native pigs multiplier project funded by the Bureau of Agricultural Research (

by NirvanaFan01234[/caption]

At the University of the Philippines Visayas (UPV), the program on the development of algal paste from microalgae under the National Aquafeeds R&D Program is currently being funded by PCAARRD and Department of Science and Technology (DOST).

The program studies three brackishwater microalgal species, namely, Tetraselmis sp., Nannochloropsis sp., and Chaetoceros calcitrans. These species, which are used in the mass production of algal paste, are cultured by batch in the laboratory and are continuously monitored for quality control.

Microalgae are small unicellular plants found in marine, freshwater, and brackishwater habitats. They are considered as one of the most important aquatic organisms for its many uses in various fields. They are also fast-growing plants, with their doubling time measured in hours.

For aquaculture, microalgae concentrates are used as feed for small zooplankters (rotifers, etc.) which in turn are fed to fish and shrimp larvae. These are produced commercially from closely controlled laboratory methods to less predictable methods in outdoor tanks or ponds. Algal mass production is dependent on algal strains, weather, and culture techniques.

Aside from aquaculture, microalgae are also produced commercially for high-value nutritional products and wastewater treatment applications.

For its culture, algae are harvested and prepared using a chemical flocculant once it has reached its peak density. Concentrated cells collected are transferred in another container for another settling process and filtered until pastes are formed.

The advantage of using algal paste is that it can be used as an alternative to on-site algal culture, especially when rations of live microalgae are insufficient. Also, microalgae paste can be kept under refrigerated condition without sacrificing the nutritional quality for several months.

Microalgal paste is an instant feed that can be applied easily for aquaculture purposes anytime for fish stock. Commercial algal paste costs US$50 to US$150 per liter paste, depending on the species.

With microalgal paste, worries on phytoplankton culture and maintenance can be reduced, if not eliminated. Algal paste as an alternative for live microalgae production will surely benefit the local industries, particularly those engaged in milkfish, shrimp, and tilapia hatcheries by lowering their production and labor cost.

Microalgal pastes are now being produced at the Institute of Aquaculture, UPV-College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences in Miag-ao, Iloilo.

The PCAARRD-DOST program, which is on its second year of implementation, is currently conducting experiments to further verify the pastes’ nutritional quality and shelf life.

by NirvanaFan01234[/caption]

At the University of the Philippines Visayas (UPV), the program on the development of algal paste from microalgae under the National Aquafeeds R&D Program is currently being funded by PCAARRD and Department of Science and Technology (DOST).

The program studies three brackishwater microalgal species, namely, Tetraselmis sp., Nannochloropsis sp., and Chaetoceros calcitrans. These species, which are used in the mass production of algal paste, are cultured by batch in the laboratory and are continuously monitored for quality control.

Microalgae are small unicellular plants found in marine, freshwater, and brackishwater habitats. They are considered as one of the most important aquatic organisms for its many uses in various fields. They are also fast-growing plants, with their doubling time measured in hours.

For aquaculture, microalgae concentrates are used as feed for small zooplankters (rotifers, etc.) which in turn are fed to fish and shrimp larvae. These are produced commercially from closely controlled laboratory methods to less predictable methods in outdoor tanks or ponds. Algal mass production is dependent on algal strains, weather, and culture techniques.

Aside from aquaculture, microalgae are also produced commercially for high-value nutritional products and wastewater treatment applications.

For its culture, algae are harvested and prepared using a chemical flocculant once it has reached its peak density. Concentrated cells collected are transferred in another container for another settling process and filtered until pastes are formed.

The advantage of using algal paste is that it can be used as an alternative to on-site algal culture, especially when rations of live microalgae are insufficient. Also, microalgae paste can be kept under refrigerated condition without sacrificing the nutritional quality for several months.

Microalgal paste is an instant feed that can be applied easily for aquaculture purposes anytime for fish stock. Commercial algal paste costs US$50 to US$150 per liter paste, depending on the species.

With microalgal paste, worries on phytoplankton culture and maintenance can be reduced, if not eliminated. Algal paste as an alternative for live microalgae production will surely benefit the local industries, particularly those engaged in milkfish, shrimp, and tilapia hatcheries by lowering their production and labor cost.

Microalgal pastes are now being produced at the Institute of Aquaculture, UPV-College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences in Miag-ao, Iloilo.

The PCAARRD-DOST program, which is on its second year of implementation, is currently conducting experiments to further verify the pastes’ nutritional quality and shelf life.

One pig can sufficiently fertilize a 100-150 sq m pond with. its manure. The water depth should be maintained at 60-100 cm. With this recommended pond area and water depth together with the right stocking density, problems of organic pollution are avoided.

A diversion canal can be constructed to channel excess manure into a compost pit or when manure loading needs to be stopped.

2. Location of the Pig Pen

The pig pen should be constructed over the dikes near the fish pond. Preferably, the floor should be made of concrete and should slope toward the pond. A pipe is necessary to convey the manure into the pond. An alternative design is to construct the pig pen over the pond. The floor is made of bamboo slats spaced just enough to allow manure to fall directly into the pond but not too wide for the feet of the pigs to slip into (thus, causing injuries). The pen should have a floor area of 1 m x 1.5 m for each pig.

3. Stocking

· Stock the pond with fingerlings once the pond is filled up with water. The recommended stocking rate are as follows:

Monoculture: Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) -2 fish/sq m (3-5 g eve wt)

One pig can sufficiently fertilize a 100-150 sq m pond with. its manure. The water depth should be maintained at 60-100 cm. With this recommended pond area and water depth together with the right stocking density, problems of organic pollution are avoided.

A diversion canal can be constructed to channel excess manure into a compost pit or when manure loading needs to be stopped.

2. Location of the Pig Pen

The pig pen should be constructed over the dikes near the fish pond. Preferably, the floor should be made of concrete and should slope toward the pond. A pipe is necessary to convey the manure into the pond. An alternative design is to construct the pig pen over the pond. The floor is made of bamboo slats spaced just enough to allow manure to fall directly into the pond but not too wide for the feet of the pigs to slip into (thus, causing injuries). The pen should have a floor area of 1 m x 1.5 m for each pig.

3. Stocking

· Stock the pond with fingerlings once the pond is filled up with water. The recommended stocking rate are as follows:

Monoculture: Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) -2 fish/sq m (3-5 g eve wt)